BATON ROUGE, La. (AP) — As public frustration over Louisiana’s violent crime grows, Republican gubernatorial candidate Attorney General Jeff Landry is backing legislation that would make certain confidential juvenile court records public in three of the state’s parishes, all of which are predominately Black.

Advocates for incarcerated youths oppose the bill with some calling it blatantly racist. They fear it would have detrimental generational effects on juvenile delinquents, some of who have not been convicted of a violent crime but simply accused of one. The advocates argue that making records public defeats one major purpose of the state’s juvenile system — rehabilitation into the community — and would risk their opportunities for employment, education and housing.

“You have a (teenager) whose brain is not fully developed and who has made a mistake. And 20, 30, 40, 50 years from now, they still aren't able to put that behind them,” Kristen Rome, the co-executive director of Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, said. “Those records are going to always be available for everyone to see ... and that creates a stigma, which creates an environment where they can’t thrive.”

, filed by Republican state Rep. Debbie Villio, proposes that all adult criminal court records be made available to the public online at no cost. The bill would also apply to juvenile court proceedings of youths 13 and older who are accused of committing a crime of violence or if they are accused of a second felony-grade delinquent act, such as robbery, theft, driving under the influence and assaulting a police officer. Currently, most juvenile court records are confidential in the state.

The bill is proposed as a two-year pilot program that would apply to three parishes — Caddo, East Baton Rouge and Orleans, all of which are home to Louisiana's most populous cities. While supporters of the legislation cited that these areas have the , they are also predominately Black.

“The confidentiality provisions were intended to protect the identity of young people from scrutiny later in life when these youthful indiscretions and mistakes might be impactful on their adult life,” said Jack Harrison, a law professor at LSU and long-time public defender in juvenile court. “But what's happened is that these provisions have shielded juvenile courts from public scrutiny .... and I think, frankly, people would be surprised to know what is happening in these courts.”

Harrison says the public would likely be shocked to learn of heightened charges pursued and overzealous punishments dealt to juveniles in the state. But some Republican politicians — who for years have campaigned with tough-on crime rhetoric, calling for harsher sentences — say they want to tamp down on possible leniency in criminal courts in a state that has the nation's

“You cannot maintain the rule of law, or dispense justice, when we are all wandering around lost in the dark,” Landry said. “This plan will expose who in the system should be held accountable for the failures; when (District Attorneys) fail to prosecute, when judges fail to act, when police are handcuffed instead of the criminals.”

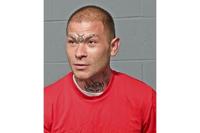

Cortez Collins, a Black police officer in Coushatta, Louisiana, understands loss at the hands of juvenile crime. Last December, his 17-year-old son, Corterion Collins, was shot and killed.

Another 17-year-old was arrested for the shooting and plead guilty to manslaughter, Collins said. He was sentenced to 3 1/2 years — the life sentencing for a juvenile. But Collins aches knowing that someday they will be released from prison and with a clean record and able to get a job without their employer knowing what happened nearly four years earlier.

“If you are bold enough to pull the trigger and take somebody’s life, I feel it should be known,” Collins said.

Landry has said that if juvenile records become public, the Department of Justice, which he oversees, would create a victim notification system to text and email individuals of upcoming court proceedings and developments related to their case. There currently is a notification system but family members of slain victims say it needs significant improvements.

Incarcerated youth advocates argue the proposal to create a victim notification system out of the bill is masking the harmful effects the legislation would have on already marginalized communities, especially as Black youths are more likely to be incarcerated than white juveniles.

“I think, in this instance, it is becoming very clear because of the locations (for this legislation) that there are certain children — particularly Black children — who we are unwilling to provide a second chance to and we quickly look at them and decide, ‘Oh, they are just not going to be better,’” Rome said.

Ashonta Wyatt, an education and social justice advocate in New Orleans, said the legislation feels like a targeted attack and that focusing on three parishes — when there is crime across the state — makes it seem as if those areas are being dubbed the “equivalent of warzones.” And while Wyatt acknowledged the high crime in New Orleans, she said lawmakers should focus on addressing the reasons behind criminal behavior rather than what is happening in courts.

“If you look at those same parishes, you will see a broken school system. You will see a lack of quality of living. You will see housing that’s unaffordable. You will see a lack of opportunity,” Wyatt said. “If (Landry) can see where there’s a need to pilot a program to target crime, then he also should be able to see that these are the same areas where he has to support the pouring of resources to help rehabilitate those communities.”

While there is no synonymous answer across the aisle on how to improve the current situation in the state, which repeatedly has one of the highest and where there are typically more than , all agree something must give.

“It’s hard because on both ends we’re losing. We’re losing because people are dying and we’re losing because our children are losing themselves to the juvenile justice system," said Wyatt. "There are no winners.”

___

Associated Press video journalist Stephen Smith in New Orleans contributed to this report.